“This is the particular theme of the pearl pictures, a gentle stillness of stature. The shape is vertical. The figure appears, tender and immaculate, out of the cleft shadow of the cumbrous furniture; it is rooted in it, rooted, as we see at last, utterly unmoving, to the floor. And besides this upright shape, this pillar, we come to know another, its antithesis that nevertheless easily and equally combines with it. It is the shape of a bell... More essentially we remember it as the shape of rounded shoulders which is often the stooping shape of preoccupation, of a woman bent attentively over a table. It has a feminine quality of self-possession..." - Lawrence Gowing Vermeer, Oakland CA: University of California Press

One of the 20th century’s leading Vermeer experts was the English artist and writer Lawrence Gowing. Knowledgeable on both Vermeer’s historical and artistic context, one of Gowing’s most noteworthy contributions to The Discourse was defining the concept of the “pearl pictures” within Vermeer’s work.

Named for their luminous approach to light, the “pearl pictures” are a group of Vermeer’s mid-career paintings noted for their similar subject matter and composition. They each feature a single woman at a table, facing a window in the left-hand corner of a room, engaging in a discreet activity, while either wearing or handling pearls.

Goring would initially identify four quintessential pearl pictures - Woman Reading a Letter, Woman with a Pearl Necklace, Woman Holding a Balance, and Woman with a Lute. Other scholars often group Woman Reading a Letter at an Open Window and Woman with a Water Pitcher into the pearl pictures, although their inclusion is not universally agreed upon.

Now, when I say that I’m a Vermeer fangirl, what I really mean is that I’m a pearl picture fangirl. Like Gowing, I am captivated by this series and its extended cinematic universe. All those bell-shaped women, like bowed tulips, gracing the canvas with their quiet introspection and soft self composure. Through repetition, you can watch as Vermeer hones his craft across the series. Whittling his visual language down to a precise, pointed simplicity.

“Even by Vermeer's standards, the scenes of these works are organized with exceptional economy utilizing a table with a single woman, a meager still life, a few carefully chosen props, a map or painting on the background wall and one or two chairs”

This is the apex of Vermeer’s art. The pearl pictures feel like individual celluloid frames clipped from a film reel. They are the pregnant pause preceding the action. A woman lost in her internal world, depicted in the half-second before the viewer’s entrance upon the scene. In them one can anticipate the interruption, the broken concentration to come. How the angles of her body and face, startled out of their self reflection, will snap back like a rubber band. Shifting their orientation under the requirements of a woman being perceived.

The way Vermeer captures this moment before the re/action feels intimate, familiar and also ripe for a feminist reading. And so the pearl pieces have become the centerpiece of my Vermeer studies.

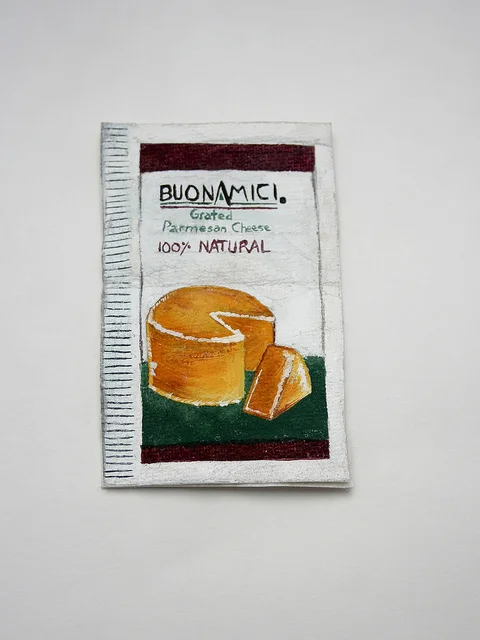

In the art studio, bent over my work table by the window, I toil alone with my pearls and my pictures. A paper bell, a silk tulip, I pantomime the actions of Vermeer’s solitary female figures, perfecting them through my own repetitions. I feel a deep kinship with them. Yes, much of it is rooted in our shared gender. But there is an important divergence – I identify with the subjects of the pearl pictures because being an immigrant is a terribly lonely business and I see myself in their solitude and self containment.

In a way, my Vermeer studies are a pregnant pause of sorts. They represent the moment between being an American artist and an American-Dutch artist. The lonely, solipsistic work of figuring out who I am and what I want to create in this new place. I am the half-second before the re/action. Waiting for what comes next in this journey of making art in the Netherlands.

Tot ziens!

🎨🎨🎨